Harlan Ellison used to say that I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream was a game that nobody could win. I gather now, having looked at a few wikis, that this is not entirely true. But back in the mid-1990s when I first encountered this weird, horrifying video game, it certainly felt true. I Have No Mouth was… not a hit, exactly, but certainly the subject of a sustained mania in my student house at the tail end of the last century. Adventure games, or point-and-clicks, were our collective favourite genre, outside of endless sessions on Worms 2. Back then we recognised that, even amongst the Monkey Islands and Tentacles, I Have No Mouth was…special?

The game is a sort of sibling to Ellison’s short story I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream, which was written in the 1960s. This is a horror story in the purest sense – it’s gloriously wretched, haunting stuff. Due to the organisational pressures of a three-way world war, America, Russia and China all build their own supercomputers to manage the movement of nukes and troops and all that radioactive jazz, and these giant machines lurk far beneath the earth in a series of caves and concealed tunnels. In the course of the war, one of the computers becomes sentient and combines with the other two. It then exterminates all of humanity except for five people, who it spends the next hundred-odd years torturing. It also keeps them alive artificially, which is, I guess, all part of the torture as well.

In the short story, these five characters head off on a journey through the underground chambers in search of tinned food. In the game, the five characters, slightly changed for the shift in format, are sent out on individual adventures – although “adventures” is far too sprightly a word for the psychodramas that unfold. The game’s just arrived on consoles for the first time in a faithful adaptation from Nightdive Studios. Nightdive’s a team that specialises in these kinds of digital resurrections of cult classics. Rather than updating this particular game for the modern era, the studio has largely played it straight.

This means that the screen still contains an action window along with a series of verbs and phrases that can be used to direct on-screen characters. (One of these verbs is “swallow”, which is a pretty good indicator of the grimness that awaits.) While there are now button shortcuts that mean you don’t have to click on each individual phrase, you will still need to highlight parts of the environment using what amounts to a mouse pointer, now controlled with a stick, and with finessing available via the D-pad.

Personal note. This pointer, combined with often tiny on-screen elements to click on, proved more than my twitchy, MS-addled hands could cope with for any length of time, but I suspect most players will find it fussy yet ultimately manageable. While I struggled to play, then, what I did appreciate was a chance to return to the memories of a game that I once spent a lot of time with, but which I’ve long since put out of my mind.

I don’t think I’d ever really played a horror game back in the mid-1990s, or if I had it was something fast-paced and shotgun-based, a game about hordes and ammo and dogs leaping in through shattering windows. Horror? That stuff would be light relief in I Have No Mouth. Each of the psychological gauntlets the game’s characters head off on is tuned to the specific flaws or regrets of their individual personalities. Gorrister, for example, ends up on a sort of horrific zeppelin where he must explore what looks like a murder scene while he slowly reexamines the guilt he feels over what happened to his wife. Ellen, meanwhile, is an engineer who must overcome her fear of the colour yellow to explore a strange technological pyramid filled with monitors and sparking electrical wires.

None of these scenarios sound particularly traumatising, but a few things come together to make the game not just memorably horrible but genuinely haunting. For one, there are the themes the game is willing to explore and the places it’s willing to take players. I was playing I Have No Mouth alongside games like Sam & Max Hit the Road and Full Throttle – genocide and mental illness, to name just two of I Have No Mouth’s preoccupations, were quite a departure from the road trips and windup bunnies.

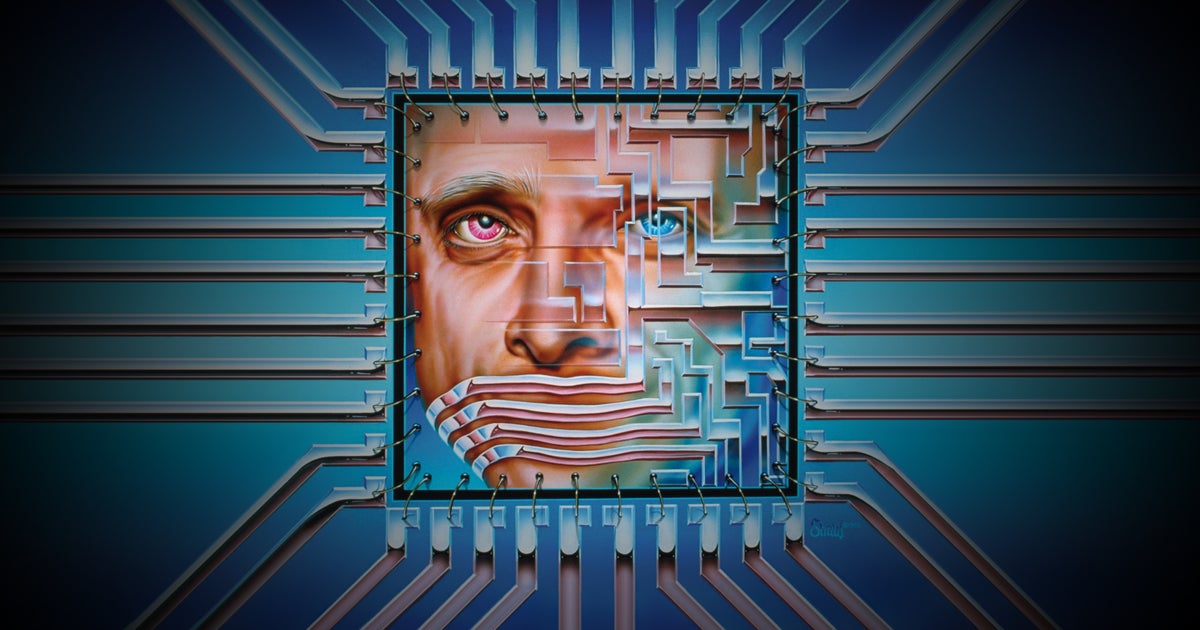

Then there’s the graphical approach. I Have No Mouth unfolds, like most adventure games, as a series of screens that the player navigates as they solve puzzles. Back in the day, it felt incredibly subversive to use the kind of visual design I was used to in games like The Dig to offer up such an array of hellscapes and crime scenes. There’s something of Bosch to the game’s depiction of a future world run by an evil supercomputer. Bodies pile up or hang from meat hooks, the ground is rumpled like the folds of a brain, and even a relatively open vista feels claustrophobic, with a ceiling that looms and a vanishing point that suggests the wet tunnels formed by some awful creature’s intestines. This stuff is beautifully done, but all the effort is bent on creating an oppressive environment. Playing for any length of time is a bit like watching too many Youtube spelunking videos. You need to go outdoors afterwards and just look at the sky for a half hour.

The most effective part of the whole thing, though, might come down to genre as much as anything else. I Have No Mouth is an adventure game, after all, and these games are famous for their fiercely limited agency. It’s bad enough being trapped in a diner with Gorrister where desert stretches off in every direction and the only person left to talk to is a cryptic jackal, but what’s worse is that, quite often, you’re simultaneously left exploring a puzzle that seems designed to leave you stumped for long periods of time. The end result is that you, like the game’s characters, exist in a kind of repetitive loop of carefully curated misery. I can’t tell whether I Have No Mouth’s puzzles are more villainous than those found in something like Zak McKracken, say, but I do recognise that they’re puzzles that are designed to feel a bit like nightmares, which means that standard logic wouldn’t really work here.

Looking back on I Have No Mouth now, while I do think about Ellison’s story and the queasy impact it had on me when I first read it, what the game really reminds me of – because of how similar and yet how different it can be – is something like David Cronenberg’s Videodrome. This is a truly stunning film in which James Woods plays the president of a TV station who grows a VCR slot in his stomach. It’s body horror just like a lot of I Have No Mouth, and yet I always find Videodrome exhilaratingly creative, while I find I Have No Mouth admirably oppressive.

That’s the point, of course, but I think this reaction of mine is ultimately down to the medium. Videodrome is a film made before CGI so there’s a playful arts-and-crafts feel to even its most terrifying visions. I look at that VCR slot, for example, and while I’m thinking, wow, that’s pretty gnarly, I’m also thinking, how did they do that? What did they use?

With I Have No Mouth, the short story, you can’t do that, because everything is made of words, and you can’t really stop and ask your own imagination whether it used fishing line and chicken wire to work its grim magic. Equally, you can’t do it with I Have No Mouth, the game, either, because it’s all pixels, it’s all made of the same stuff, and so the horror, while lacking in visual fidelity, has a kind of rigour and authority because it’s made of the same things as everything else.

That’s the core of it, I reckon: both short story and game offer visions of reality from which it’s very hard to escape. You can put the book down, and you can turn off the console – or, if you’re particularly determined, you can puzzle your way through to the “good” ending Ellison would pretend didn’t exist. But in the days, weeks, months and years that follow, some part of you is still trapped back there with those words and those images.

Code for I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream was provided by the publisher.