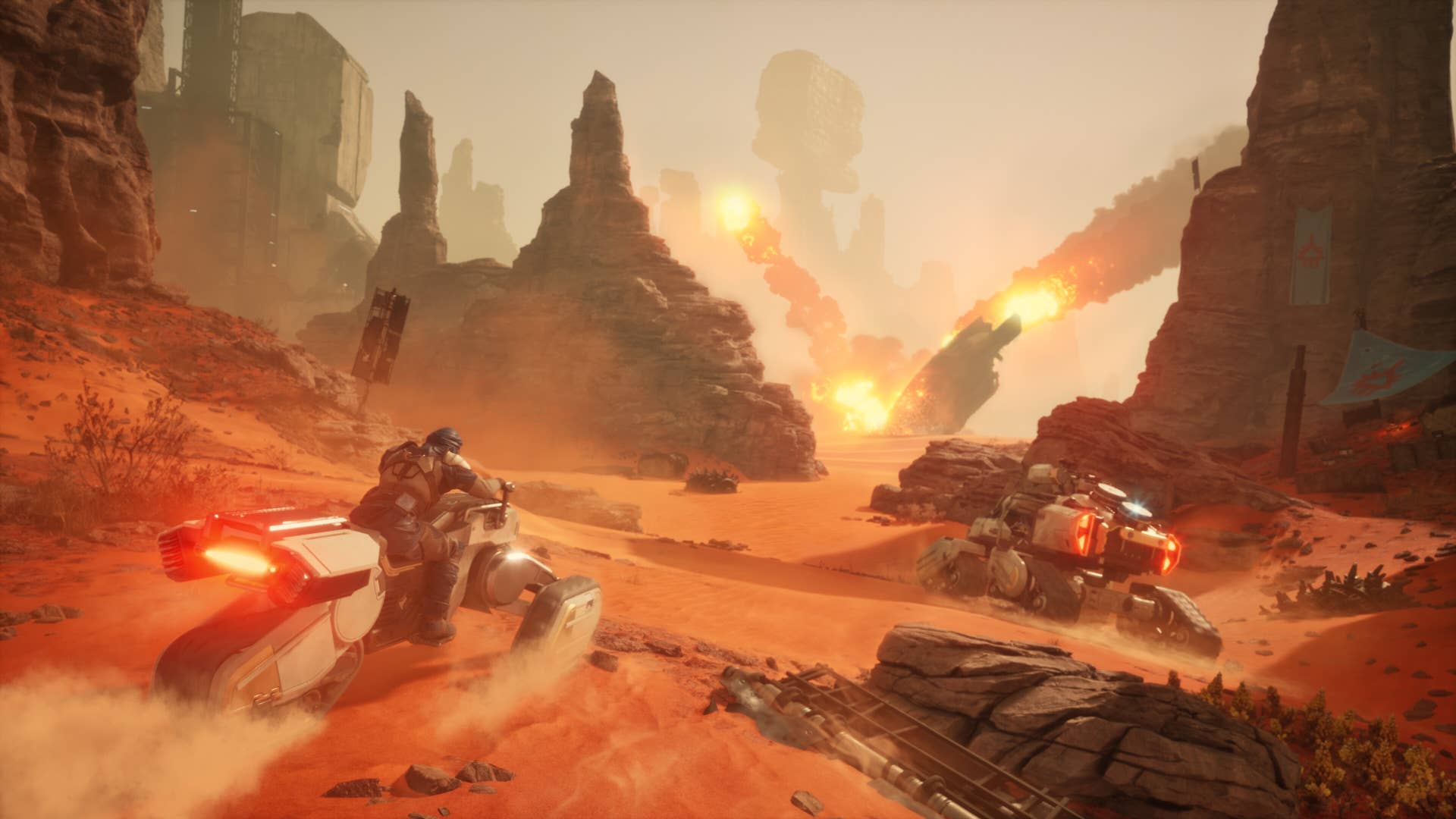

As I leave my little granite box of power generators, fabricators, refineries, and a bookcase – my humble, frequently extended base-for-one in Dune: Awakening – I reflect on the ritual I perform. Check that my equipment has enough durability left, fill a literjon with water, pack a stilltent. I clamber up a sheer rock face, staying within the moving shadow of the cliff to avoid heat stroke and sipping on the water collected in the catchpockets of my stillsuit, a piece of desert bondage that traps and recycles my moisture.

It may not be as strict as the Fremen water discipline described in Frank Herbert’s novels, but Awakening’s punishing conditions lead me to internalise its systems – not simply to roleplay like a Fremen, but to inherit their traditions in order to get the most from my time in the desert. This is the game’s greatest strength. Dune II remains my favourite Dune adaptation, but Awakening is, by far and away, the most faithful. Yes, there are concessions to gameplay – the Imperium didn’t have a special device to tuck vehicles away in a pocket, for instance – but it is a remarkably lore-first approach.

But just how faithful is it, I wonder? Dune is a notoriously difficult series to adapt, not least because there is no consensus regarding what the Dune canon consists of. Some fans swear by the original book only; others acknowledge the first three; some (including me) worship at the altar of the God Emperor; a certain kind of masochistic heretic even manages to glean enjoyment from Kevin J. Anderson and Brian Herbert’s monstrously expanded universe.

It is difficult, too, because of the series’ knotty plotlines and strange world-building. This is a universe where human minds can be trained to perform complex calculations at the speed of an advanced machine, where foetuses can awaken in the womb and speak to their mothers, and where tank-swimming drug addicts use precognition to navigate space instantaneously.

Dune: Awakening understands most of this. It uses the same “cold open” as Frank Herbert’s first novel. Much like Paul Atreides, with minimal exposition or explanation, you are dropped in front of a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother and her Gom Jabbar test, which doubles up as an ingenious diegetic device for the game’s role-playing character creator. It’s indicative of the game’s broader approach to gameplay. The book doesn’t coddle the reader, expecting them to immerse themselves in its world-building before things start to make sense. Just so, the game doesn’t coddle the player, removing things like suggested player levels for different regions and fast travel to encourage immersion into its systems before they can be fully exploited.

Although the ending of the second part of the story does pay off in spades, having role-played an Ixian Bene Gesserit-trained Harkonnen, I would have liked things to get a bit more weird than merely a few different dialogue options. And the gentrified sprawl of player-created bases, together with the 1950s vibes of the optional radio stations, spoil some of the vibe.

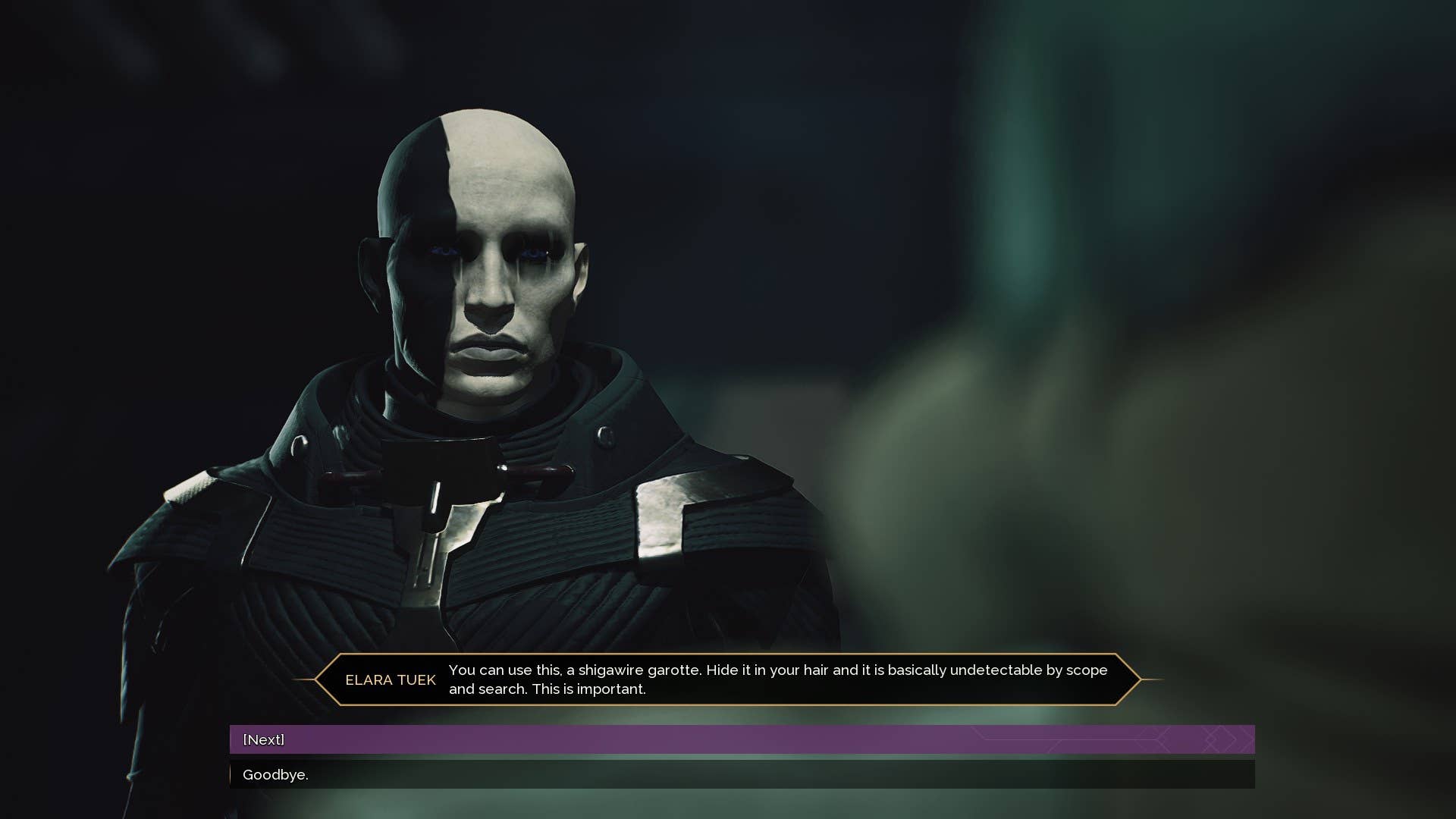

By and large, however, Awakening is in reverence to its source material. Chaumas poison, crysknifes, elacca narcotics, fremkits, glowglobes, Holtzman fields, pentashields, sandcrawlers, servoks, shigawire, sinkcharts, solido projections, suspensor belts, and many, many other small details of Herbert’s rich world find a meaningful place in Awakening, alongside some of the bigger concepts, like the rules of a Kanly feud or the Bene Gesserit Missionaria Protectiva. Even the kulon, Earth’s donkey adapted for the harsh climes of Arrakis, trots its way into the game.

In some ways, this level of fealty to the lore is unsurprising. In a recent livestream, Creative Director Joel Bylos described how the game’s dew-gathering mechanic was based on a single passage from Herbert’s novel. He explained that the team’s approach was to look at how survival mechanics can fit the Dune universe, rather than the other way round. Meanwhile, the aesthetic is an eclectic mix of Denis Villeneuve’s minimalist geometry, David Lynch’s sweaty baroque, the on-a-budget campness of the TV mini-series, and Funcom’s own take on the setting. There are some pleasant callbacks to the older games, too, like nods to Dune II’s Light Infantry in some of the armour design.

Given all this, then, it is surprising how much Awakening struggles with Herbert’s grander, more abstract themes. My sense is that this is almost entirely due to the absence of Paul Atreides. Awakening is set in an alternate timeline, where Lady Jessica obeyed the Gene Gesserit breeding programme and chose to give birth to a girl. It is a smart move in terms of ditching the expectations of the novels, freeing the game up for original and unexpected storytelling. And yet Paul Atreides is the linchpin for the series’ broader philosophy.

Although Frank Herbert had some of the initial ideas for Dune in the late 1950s, he wrote it in the age of John F. Kennedy, and said that the novel was in part a warning against the dangers of charismatic leaders. Paul is exactly that kind of leader. Noble, principled, just, his ascendancy was nonetheless disastrous for the galaxy. It brought a holy war that turned into a genocide far greater than anything perpetrated by the overtly despicable House Harkonnen or decadent House Corrino, and eventually put his son on the imperial throne, who ruled for thousands of years as a tyrant. And while it might be easy to mistake Dune for a “mighty whitey” saviour narrative, Paul’s reign in fact rewrote and ultimately destroyed Fremen culture. There is no analogue for this in Awakening. There are plenty of leaders corrupted by power and the plans within plans of the Kanly feuding that grips Arrakis, but not the kind of singular failure of leadership that nudges an entire planet towards fanatical murder.

One could argue that Paul was locked into the Golden Path – the optimal route through future history that would avoid or at least delay human extinction – the moment he became the Fremen’s prophet, and that the path was inescapably laid with death. I am not convinced this is true. Paul’s greatest personal failing was his rageful desire to avenge the death of his father, and the knowledge granted by his prescience that he could use the Fremen to achieve this, but that in so doing he would step onto the Golden Path. Herbert’s argument, as I see it, is that Paul was too weak to walk away when he still had the ability to do so.

Irrespective of whether I am right or not, however, the salient point here is that there is a knot of thorny philosophical questions of determinism, the greater good, human progress, and decadence wrapped around Paul’s actions. Awakening does touch on some of this. The Bene Gesserit conditioning your character is subjected to raises some intriguing questions about your free will, for example (and perhaps a meta-narrative about choice in video games more generally), while allusions to the Missionaria Protectiva imply religious manipulation. But the game doesn’t tackle the larger themes of destiny, evolution, or cultural decay.

Paul’s Golden Path also involved the terraforming of Dune into a water-rich world. Awakening does address this more so than almost any other adaptation (with the exception of the TV mini-series). There are Imperial Testing Stations dotted around the game world that show evidence and relay stories of terraforming efforts. Yet they lack the full subtlety of the novels. Herbert dedicated Dune to the “dry-land ecologists”. He was deeply interested in systems thinking and ecological collapse and renewal – something that’s clear, for example, from the manner of the Imperial planetologist Liet-Kynes’ death in the book: as he waits for a Spice blow to take him, he considers at length Arrakis’ ecosystem.

Paul’s control of Arrakis also exposed the fragility of monopolies, the complacence that comes to unchallenged regimes, and their dependence on trade and capital. He won ultimately because he choked Spice production and thereby the Spacing Guild, who cannot travel without the Spice. It is a curious bit of prediction on Herbert’s part – a world in thrall to trade interests above all other considerations – and, again, one that is largely missing from Awakening. Indeed, there is a sense in which Awakening’s plurality of guilds and, with them, Spice mining operations in the Deep Desert, stands in contrast to the monopolisation of Spice production in the novels.

In short, Dune: Awakening is a curious study in adaptation. On one hand, it is reverentially faithful to the source material, transplanting more of its lore and world-building than almost anything else I’ve seen. On the other, by pivoting into an alternate timeline, without characters that are key to the series’ themes, it loses a lot of the books’ deeper meaning. As such, I wonder if it is ultimately best viewed not as an adaptation or interpretation, but as a re-imagining. And perhaps that is enough. To borrow one of Paul’s sayings, “Arrakis teaches the attitude of the knife – chopping off what’s incomplete and saying: ‘Now, it’s complete because it’s ended here.'”