My time at university is bookended by moments that changed my idea of what games could be. When I started my first year, I saw Tomb Raider running on an upside-down PS1 in someone’s dorm and I was stunned and sort of disconcerted. My 2D gaming mind had no idea how to understand a game that seemed so comfortable in three dimensions, but which also – after years of seeing increasingly refined pixel art – seemed so comfortable with being so ragged. The gaps in Lara’s polygonal joints. The clipping of 3D surfaces. The way the polygons around the sides of the screen sometimes disappeared giving the image the perforated edge of a postage stamp. Was this a step forward or a step back?

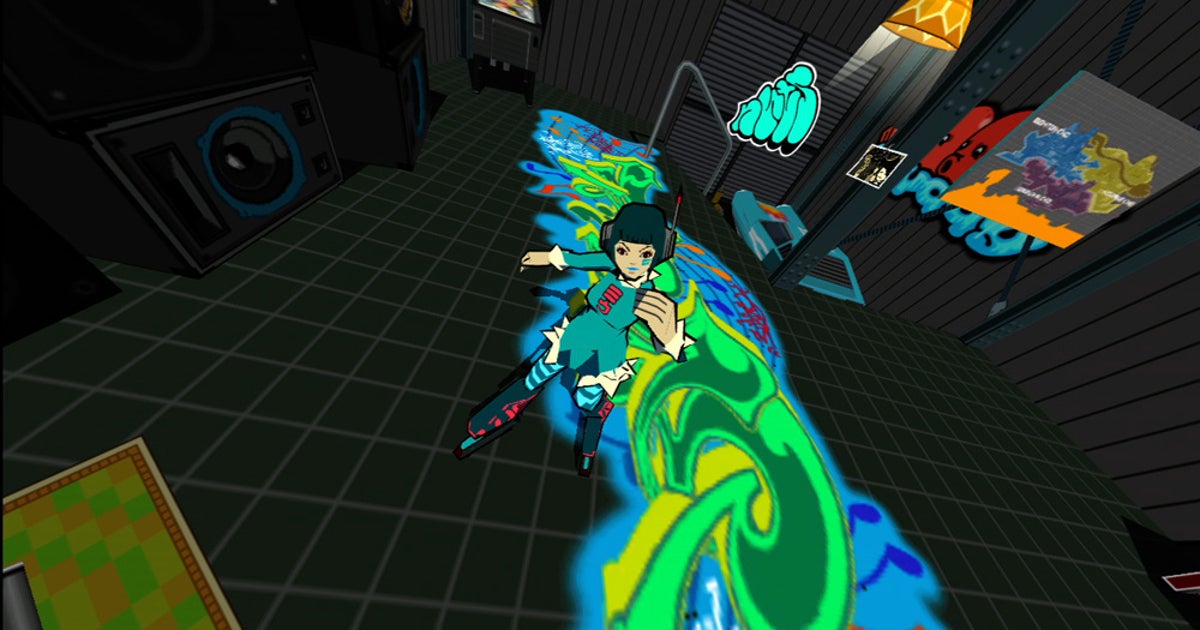

Then, just after my final year: a friend’s house, a Dreamcast and Jet Set Radio. The colour, the flat shapes – the Cel-shading! The sense of a graffiti aesthetic carried all the way through a game to its rigging and its bones. I will never forget that glimpse of a game, and my sheer disbelief that it was a thing that moved, a 3D world, and not a gorgeous static image.

Bookends. And we start with one concerned with the power of new perspectives and a way of physically being in a game’s space, only to end with one concerned with the power of representation, style and surfaces.

Somehow, then, this was 25 years ago. This means Jet Set Radio is 25 years old – right now, I gather. And in a way this makes sense: few games are so engaged with their visual look and their sense of the ways in which style roots you in a time and a place. So yes, Jet Set Radio fairly screams 2000 to me. But also, few games feel – well – kind of timeless. In their art? Yes. In their mechanics? Less so. But in their sense of what games were becoming, and what games could be? Absolutely.

I’m going to talk about Jet Set Radio and its sequel Jet Set Radio Future today, because it’s the series, in my mind, which is 25 years old, and these games are two halves of the same sentence to me anyway. Jet Set Radio set out a world in which skater gangs could fight not to save the world but to save a way of life in a wonderfully topical-futuristic spin on Tokyo. Jet Set Radio Future doubled down on the sense of place, situating the heart of the series in an engagement with place and movement more than challenge and traditional game design. As a whole, I reckon few games offer as pleasing a case study on the process of focusing in on what truly matters in a piece of design – and following the design’s special desires even when they lead you into some odd territory.

And it’s a pretty simple story in one way. I can express it in a sentence. Jet Set Radio’s levels had timers and Jet Set Radio Future’s didn’t. But why does that matter so much? Why does the removal of a fairly standard game design open something up to its true potential?

It’s because Jet Set Radio’s world and characters were already intoxicating. These colourful, angular heroes and the cool subculture they came from. The dense, complex neighborhoods filled with cool little stores and canted advertising hoardings everywhere that they moved through. These things were clearly the big deal here, and yet Jet Set Radio was a game about project management as much as it was about exploration.

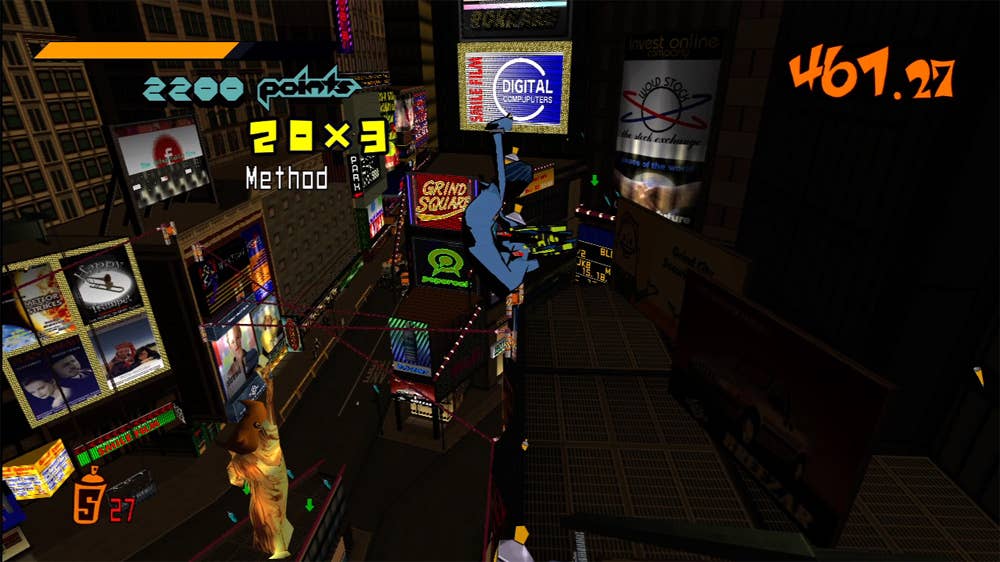

Sure, you had to explore the environment to cover specific spots with graffiti and therefore finish a level. But you had to do it all within a set time, too, and while enemies attacked and wasted that time. So you explored and failed, explored and failed, memorised and perfected a route and eventually succeeded. But at that point you were firmly in a game rather than a place. You were in the world of objectives and missions and restarts.

No timer in Jet Set Radio Future, and so you could suddenly take as long as you wanted. You could stop mid-level and just watch your character dance. And you could poke around some of the emptier, more pointless corners of some of the most brilliant video game maps ever created, only to discover they weren’t empty or pointless at all.

Why? Because they’d always have something cool or colourful there that grounded you in a specific place. There would be a memorably dressed pedestrian or a cool building or a grind rail or a chance to dance between satellite dishes. Jet Set Radio always wanted to be this: a place and a way to move through this place that felt freeing, exhilarating, and not too technical. Suddenly the series was free to be itself.

And I think you can see this extended outwards in games that borrow from Jet Set Radio and Jet Set Radio Future. In some ways, its influence is everywhere. From Splatoon to Sunset Overdrive, it’s become the kind of deep cut that the best fan-turned-musicians love to sample.

But the influence is at its clearest in Bomb Rush Cyberfunk, a recent game that had a simple premise: more of the exact same? More graffiti and urban exploration? More Cel-shading and jittery, restless radio for the soundtrack? More movement and place?

And what’s interesting about Bomb Rush Cyberfunk is what it spends its energy on and what it doesn’t. Timers? No. More complex missions? Not really. Larger spaces, but also smaller, more tricky spaces? Absolutely yes. And a handful of tweaks to movement – an air-shunt, the ability to lean on a grind and grind from above as well as below – that make the whole thing easier to sustain. You can keep movement alive pretty much forever in Bomb Rush Cyberfunk.

It makes me wonder, this paring down, of where the original series would have eventually ended up if there were five games rather than two, say. I know we’re meant to be getting a new instalment soon, but what if we’d have a bunch of new instalments that followed the immediate thought processes of those first two games.

I suspect we would have continued to see less rather than more. Less challenge. Fewer things to stop you and keep you busy or engaged in typical video game stuff. And more movement, and more of an environment that was eager to collaborate with your movement. You would be a bright blur of cel-shaded light, always coasting on, never stopping. Happy birthday, Jet Set Radio.